Boy Scout California Store Peoria IL

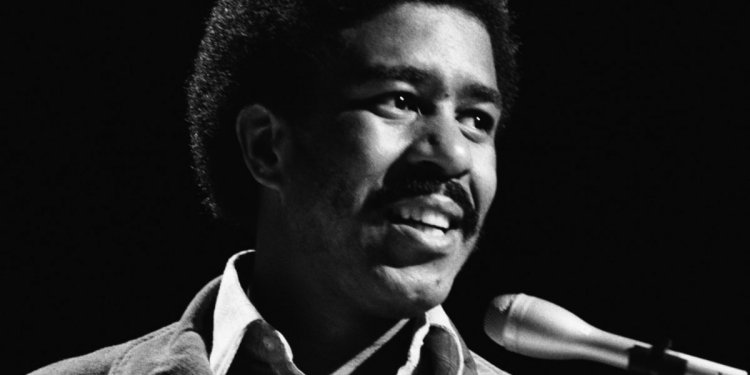

The man who nimbly scales the steps of this renovated caboose cabin cannot be 95. As he drives us around Scott’s Prairie—70 private acres of land in Hanna City he gifted to the Children’s Home—he defies age with a detailed recall of decades-old memories. Born in 1920, Bob Gilmore grew up in Peoria during the Great Depression. He graduated from high school in 1938, landed an apprenticeship at Caterpillar, and worked in the shop before enlisting and serving 30 missions as a B-17 Air Force navigator in Europe. Returning to Caterpillar in 1946, he quickly ascended the management ranks.

The man who nimbly scales the steps of this renovated caboose cabin cannot be 95. As he drives us around Scott’s Prairie—70 private acres of land in Hanna City he gifted to the Children’s Home—he defies age with a detailed recall of decades-old memories. Born in 1920, Bob Gilmore grew up in Peoria during the Great Depression. He graduated from high school in 1938, landed an apprenticeship at Caterpillar, and worked in the shop before enlisting and serving 30 missions as a B-17 Air Force navigator in Europe. Returning to Caterpillar in 1946, he quickly ascended the management ranks.

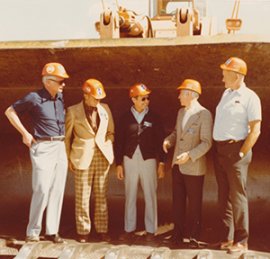

In 1963, Gilmore was asked to open a new plant in Grenoble, France, and successfully grew the facility over five years, the project a catalyst for Cat’s future international endeavors. He returned to Peoria with his wife, son and daughter in 1968 and became vice president for the 10 plants in the company’s U.S. operations. Gilmore became president in 1977, amidst a period of record sales and profits. But in 1982, the bottom fell out of the construction equipment market, and the company was forced to lay off 14, 000 workers and close four plants. By the end of 1983, layoffs totaled 35, 000 and nine plants closed. Approaching retirement age, Gilmore refused to leave until the company was back in the black—a huge accomplishment of which he is most proud in his long career. Honored to have spent a lifetime with Caterpillar, Gilmore defines himself as “yellow-blooded”—the evidence of his love for the company under his skin.

In addition to his hard-working spirit, his legacy will live on in the community he has served far into his retirement, through the Society of Manufacturing Engineers, Peoria Area Chamber of Commerce, Masons – Temple Lodge, Peoria Consistory, Mohammed Shrine, Country Club of Peoria, Creve Coeur Council of Boy Scouts of America, Economic Development Council and the Rice Pond Duck Club, among others. In May, he invited iBi to Scott’s Prairie to chat in the caboose car he spent three years renovating with his late son, Scott.

Tell us about this beautiful property!

I bought it in 1980, and it was a wasteland… I sought it out with the idea of just using it for hunting… rabbits, [ducks], squirrels and quail… The rest of the property was rental property, which was pretty well run down, and the longer I had it, the more I thought there were other things I could do. That’s all I wanted for it really, [but] old-growth timber is pretty hard to come by these days… Just ten years ago, I gave it to [Children’s Home].

What was it like growing up in Peoria?

I was born and raised in Peoria, and these were pretty tough days. I was born in 1920… so the primary growth years for me were in the depression years. [They] were pretty tough years economically, so there was no chance of me going to college. As a matter of fact, I worked in a dairy every summer all through high school… I thought I had a career doing that, but the dairy merged about a month after I got of high school, and I lost my job (laughs). So I walked the streets for six months, and finally got a job at Caterpillar making 32 cents an hour.

And what were you doing for them?

I was a beginning apprentice. I spent four years as an apprentice, at which point I got a diploma as an A1 machinist and was raised to 85 cents an hour.

So, where did you go from there?

Well, I graduated from the apprentice course… Caterpillar had just gotten a huge defense contract for transmissions for tanks… My first job when I got out as an apprentice was hand-building the first two or three hundred, single-mesh clutches… I was out in the shop for a year or so. But this was now 1942 or ‘43, and all of my friends were gone [to war], and I was pretty healthy at 22 years old. I had gotten multiple deferments because of my work on this military project, and I really got tired of getting deferred—it was embarrassing… [My boss] said I was really more valuable to the company and this special project. So I quit… Patriotism was a major element for people at that point in time. You just didn’t feel [good] if you weren’t along with your companions… and I was in the shop with a lot of older guys who had children, but their kids were in the Army or in the service somewhere. I really can’t say whether it was patriotism or peer pressure or all of those things, really, but I quit, which then caused the company to automatically give me military leave…

I went off to Fort Sheridan to join the infantry. I was standing in one of the many lines [and] a sergeant came by and said anybody who would like to go to the Air Force rather than stand in line, go to that tent over there, which I did. I passed that test, and that’s how I got in the Air Force.

Tell us about your missions in the Air Force.

I got there just in time for the Battle of the Bulge… It was the biggest battle of the war other than D-Day. I flew my first mission, I think, on January 2nd or 3rd of 1945… We were shot out by Flak [German anti-aircraft and anti-tank artillery guns] on our first mission, which knocked us out of formation. As a navigator, I had to find a way home because instead of 30 ships, we were by ourselves, flying on three engines. We made it, and flew again the next day… [On] our third mission, we flew Berlin, and Berlin was very, very heavily equipped with anti-aircraft guns... On that mission, we just got clobbered—we lost a lot of planes… The navigator’s job was to keep track of what planes got shot down, identify them by the number on their tail, how many people got out…

The point I’m attempting to make was that every one of us was too busy to be scared. This was pretty early in our experience. We knew what we had to do. We knew we had to go to a briefing after the mission was over and accurately describe who got shot down and who didn’t… Well, about our 12th or 13th mission… we went back to Berlin again, but this time, the fear had set in. It’s amazing how we were in terrible trouble that first mission and were too busy to be scared, but our knees were knocking [when] we found out we were going back there again… When you do that 30 times, it’s a pretty demanding chore.

I imagine the transition back to the manufacturing world after the war must have been difficult.

I came back to Caterpillar on third shift in the machine shop—and that’s pretty miserable to come [back] to… I was all ready to quit, and I thought I would go through [college on] the GI Bill… With the defense background I had and with the military schooling, I figured I could get a degree in a couple of years. Well… my boss said [to] wait it out a couple of weeks and maybe something better will come up, and it did. So, I went out of the shop and into an office, and in four years, I had gone through three levels of management, from supervisor to superintendent to manager. I went from a lifetime of being a shop guy to being in the office and getting rapid promotions. But my grammar was terrible, I chewed tobacco… I was a shop guy… I was delighted to be able to do it and the job was great, but it was an entirely different environment than that in which I was brought up.