Norman Rockwell Boy Scouts California plates

American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell

by Deborah Solomon

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 493 pp., $28.00

1.

At the time of his death in 1978 at the age of eighty-four, Norman Percevel Rockwell (who had always hated his fancy, “almost effeminate” middle name) was one of the most popular artists in America and one of the most maligned. Despite the championing, late in his career, of, among others, John Updike and Andy Warhol (who, not surprisingly, bought Rockwell’s portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy), and a retrospective exhibition that traveled to seven US museums including the Guggenheim between 1999 and 2002, the suspicion has lingered—and Rockwell himself was not immune to it—that perhaps he shouldn’t have been considered an artist at all, as opposed to an illustrator (as he called himself in his charming memoirs) or, worse, a hack purveyor of kitsch, churning out his annual calendar design for the Boy Scouts or, for Hallmark, a Christmas card of Santa asleep on the job.

Did Rockwell’s principal artistic achievement, his 323 designs for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post from 1916 to 1963, really amount to a body of work comparable in any significant way to Edward Hopper’s, say, or Jackson Pollock’s? Or was he merely an ingratiating epigone to the Golden Age of Illustration, rounding off, during an era of photography, the waning narrative tradition of his idol, the Quaker depicter of pirates Howard Pyle, and Rockwell’s immediate predecessor at the Post, the now forgotten Joseph Leyendecker, creator of the Arrow Collar Man? Rockwell had nothing against modern art and considered Picasso “the greatest of them all.” He gamely, if one suspects not very seriously, tried his hand at Fauvism and abstraction, only to be reminded by his editors of his true audience.

To complicate matters, it isn’t entirely clear what Rockwell’s body of work consists of. Was it the published covers themselves, the designs often straying outside the frame and artfully incorporating the name of the magazine? Or was it the painstakingly executed oil paintings on which the covers were based, carefully framed like Dutch Masters, darkened with seemingly antique layers of varnish, and delivered by hand to the offices of the Curtis publishing firm in Philadelphia, only to be given away afterward or put aside as of no value? “I got paid for it once, ” he told a dealer, in 1968, who had offered $2, 500 for a painting already “bought” for a cover design by the Post. “I don’t need to be paid again.” Three such paintings will be auctioned off at Sotheby’s in December and—such are the changing fortunes of Rockwell’s reputation—one of them, Saying Grace, is expected to fetch upward of $15 million.

Like the work of other artists once dismissed as producers of nostalgic Americana—“big paydays for small-town mush, ” in the caustic phrase of Benjamin DeMott, who also mentioned Frank Capra and Thornton Wilder—Rockwell’s paintings have become more interesting over time. The old battles over what should be excluded from the “canon” have waned, while Rockwell’s narrow world of mainly white, WASP, small-town New Englanders, reinforcing the ethos and readership of the Post, can now be seen as an invented construct comparable to Georgia O’Keeffe’s lapidary West. Peter Schjeldahl, enthusiastically reviewing a traveling exhibition of Rockwell’s work in 1973 for The New York Times, noted the convergence between Rockwell’s photography-based work and the Photo-Realists, “the most radical wing of current American painting, ” and concluded, “the gap between Rockwell and modernism is just a gap, not a battle line.”

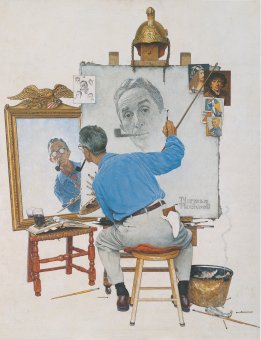

As their topical subjects recede—the GIs returning home and the girls in curlers preparing for the prom—we are free to register how Rockwell incorporated abstraction into his designs, as the art critic Deborah Solomon notes in her sympathetic and probing new biography, as well as autobiographical allusions. “The thrill of his work, ” she contends, “is that he was able to use a commercial form to thrash out his private obsessions, to turn a formula into an expressive personal genre.” The carefully contrived clutter of Rockwell’s interiors—sometimes clues to a narrative though not, apparently, always so—can recall the boxes of Joseph Cornell, about whom Solomon wrote an excellent biography, or the crowded staged interiors of the photographer Jeff Wall.